The Hungarian premiere of The Golden Dragon (Der goldene Drache), composed by Péter Eötvös, one of the most prominent composers of our time, was the highlight of the Bartók Plus Opera Festival in Miskolc this year.

The first performance of the work took place in Frankfurt in 2014, with the composer conducting. Then it was performed in Austria, Germany, Wales, England, and this year in Israel. It was the latter production seen now by the audience of Miskolc.

The libretto was written by the composer, based on the popular play of German writer Roland Schimmelpfennig (b. 1967).

*

As expected at a premiere of a contemporary chamber opera, at the end of the evening a part of the audience was celebrating, while the other part was sniffing, what is more, was outraged. But at least no one remained indifferent.

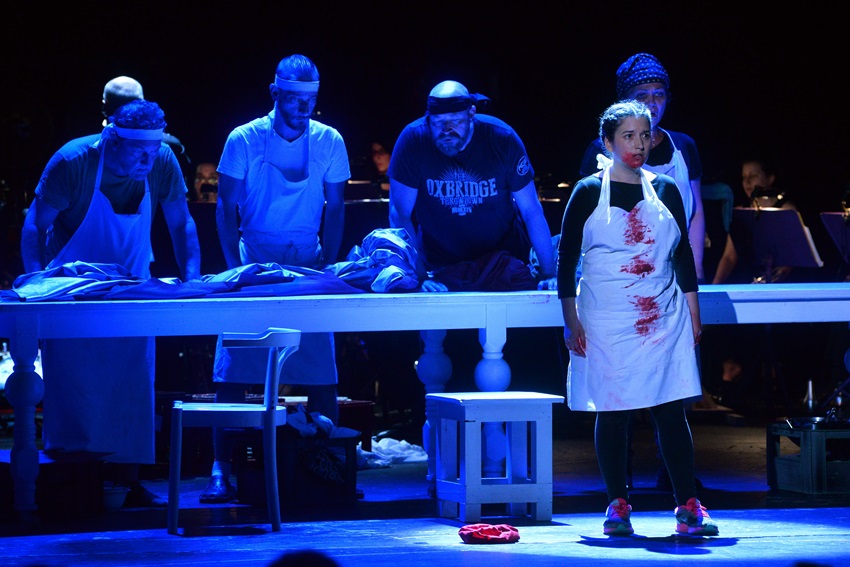

The cooks (Andrew Mackenzie-Wicks, Andrea Meláth, Kornél Mikecz, Daniel Norman)

and The Little One (Einat Aronstein) (photo: Mihály Samu Gálos)

The Golden Dragon – the genre of which was defined by the composer as ’music theater’ – is a grotesque, absurd ’sociodrama’. A dark comedy, in which burlesque and parody-like scenes alternate with melancholic, sad lyrical parts. The surreal story, interlaced with black humour, is funny, sarcastic, yet shocking, while its conclusion is moving.

*

At the heart of the plot is a Chinese boy nicknamed The Little One, who illegally stays in a German city. The boy has unbearable toothache, but since he has no official documents, he cannot get medical help. His colleagues, who work in the Asian restaurant called Golden Dragon, try to pull his tooth out, but the boy is bleeding to death. Only his dead body thrown into the water arrives home to China.

Of course, the story is more convoluted. In the libretto, the composer divided the original drama into 21 short scenes with multiple plot lines. These parallel stories interact – sometimes in an unexpected and fantastic way –, and slowly it all makes sense: the characters, having different fates, live in the same building, above the restaurant.

The Cricket (Andrew Mackenzie-Wicks) and the Ant (Andrea Meláth) (photo: János Vajda)

In the first scene, we get to know the cooks of the Chinese-Thai-Vietnamese restaurant and the Chinese boy, the Little One, who also works there. The kitchen scene then returns several times, creating the centre of the plot. Meanwhile, new scenes come, other characters appear, interrupting the ’story’ of the cooks. (Due to this deliberate dramaturgic tool – the retardation – the audience is more and more eager to see that bad tooth pulled out…)

The other important thread of the narrative is the appearance of the Ant and the Cricket. We see Aesopus's tale really twisted. The humble Cricket, which plays music throughout the Summer, now comes on stage in high-heeled shoes (it is a girl, but played by a male singer). Winter coming, she begs the Ant for food. But the elegant Ant, wearing a hat and working diligently on a typewriter, cruelly humiliates her, makes her dance, rapes her together with others, and finally tells her to go back to China. It becomes clear only now that the Cricket is actually a migrant Chinese girl forced into prostitution. This transformation is realized masterfully by the composer-librettist: the transfiguration of the symbolic, bizarre fairy-tale characters into human beings happens almost unnoticed to us.

The Grandfather (Andrew Mackenzie-Wicks) (photo: Mihály Samu Gálos)

There is also a perverted grandfather in the story, who – after he fails in bed with the already mentioned Chinese girl – tears off one of the Cricket’s tentacles in anger. The grandfather also has a lust after his pregnant granddaughter, who is in turn humiliated by her boyfriend: when the man learns that his girlfriend is pregnant, he tells her with a snarl that he is disgusted. Ultimately, this man also takes his anger out on the Chinese girl: he rudely abuses the Cricket dancing clumsily for him.

Two ‘stewardesses’ also appear (both are played by men), who dine together after a long journey. However, the removed tooth of the Little One lands incredibly (and disgustingly) in the Thai soup of one of them.

The boyfriend of the granddaughter (Daniel Norman) and the granddaughter (Andrea Meláth)

(photo: Mihály Samu Gálos)

Sometimes the Chinese relatives also speak from the distance: they worry, as they have not heard from the boy for a long time.

After the Little One dies of the tooth extraction, his body is screwed into a carpet and thrown into the river by the cooks (while one of the stewardesses also throws the tooth into the water). In his farewell, the spirit of the already dead boy tells his relatives about the long journey of his gradually decaying body through the seas to China. It is touching how he comforts his family, saying that he could save some money by getting home so cheaply… When he mentions sadly that he could not find his sister, we see the Chinese girl (the Cricket) forced into prostitution at the corner of the stage, and we realize that she is the sister of the boy, and they lived in the same house.

*

The combination of the suddenly alternating scenes of different atmosphere gives the audience the impression that the piece is both comedy and tragedy. Péter Eötvös is uniquely able to combine these two genres. He presents heavy topics in an easy tone, which shows his exceptional sense of dramaturgy. The opera is funny, entertaining, at the same time spooky and creepy.

However, this has its price. The different scenes generate adverse emotional effects, often extinguishing each other, and confusing the audience. By the time we get into watching an entertaining work with funny situations, the next scene is already coming, but this one is grim and horrible. Nevertheless, by the end of the work everything becomes clear: the threads of the plot are woven together, and it is only then that we begin to understand what exactly happened and who was who in the story. In retrospect, the work gives the impression of a unified whole, in which comedy and tragedy, good cheer and sadness fit well. What’s more, that is exactly why the story seems authentic, as it shows how diverse and controversial events, situations and people can be in real life.

The Waitress (Andrew Mackenzie-Wicks), Inga, the blond stewardess (Kornél Mikecz)

and the brunette stewardess (Daniel Norman) (photo: Mihály Samu Gálos)

Of course, in terms of its final message, this tragicomedy is shocking and depressing. Through the fate of the Little One and the Chinese girl, the work presents the vulnerability of people facing life in an unknown world, and the indifference and hostility of those exploiting them. Important and thought-provoking is the short scene, being a little separated from the centre of the plot, in which the two stewardesses are traveling on an airplane, and one of them takes notice of a crowded small boat, apparently carrying refugees. However, her colleague reacts in disbelief, saying it is not possible to see them at that distance…

We know about them, but we can't see them because we don't want to see them.

The duration of this one-act opera is 90 minutes. Despite the fast moving, quickly changing scenes – snapshots – I found it a bit long. From about two-thirds of the work the themes and the situations seem to be repeated too often, testing the patience of the audience.

We see mostly ugly, grotesque figures who are hardly lovable. The music is not ‘nice’, either, in the traditional sense of the word, but it was probably not written for this purpose. Rather, the composer wants to amaze, shock and make us think. He sometimes scandalizes, too (for example, the cooks talk at length about the look of the bloody, carious tooth, and the Cricket is humped on the stage by many, one after the other). Of course the work does have an effect on our emotions, as well: it is poignant, sad, but never sentimental.

*

In the first half of the work the percussion instruments dominate - they rattle, jangle and bang. As we move forward in the ever darker story, there is an increasing emphasis on the strings, and the music becomes more cloudy, melancholic and lyrical. Sometimes we hear oriental effects (but only imitating that atmosphere, for example, by using a gong). The declamating, parlando vocal lines do not evolve into arias, except perhaps the farewell, that is the closing monologue of the Little One. The chords and short fragments of melodies follow each other in rapid succession. They are often played only on a single instrument, resulting in an airy orchestral sound. (The orchestra is relatively small, consisting of 16 musicians.) We hear a series of carefully constructed, meticulously elaborated miniature compositions, but the musical language of the work in general is not easy to accept for the operagoer being used to more melodic, tonal music.

*

We enjoyed this both musically and dramaturgically very well composed opera in a first-class performance.

It requires virtuoso abilities from the orchestra. The excellent contemporary music ensemble, the Israel Comtemporary Players – which was now situated on the stage – brilliantly overcame the difficulties of the score, under the baton of Zsolt Nagy.

The performance of the piece for the singer soloists is no less a huge task. Primarily it is rhythmically difficult to reproduce the vocal parts accurately. I suspect that the soloists had to keep counting, because these rhythms can hardly be sung just by ‘feeling the music’. (By the way, sometimes the orchestra members also speak: ’Short pause!’ and ’Long pause!’ – they murmur with irony.) All the singers were committed and focused, singing accurately and with good diction. Their acting didn't leave much to be desired, either. They have to change clothes (except for the Little One) after each scene, changing role, but often gender, too. The singers played their roles with empathy and with a good sense of humour, when it was needed. (In some scenes they even reminded me of the Monty Python group.)

The cooks (Andrew Mackenzie-Wicks, Kornél Mikecz, Daniel Norman, Andrea Meláth)

and The Little One (Einat Aronstein) (photo: Mihály Samu Gálos)

A real international company came together for this production: the singers were mezzo-soprano Andrea Meláth and baritone Kornél Mikecz from Hungary, soprano Einat Aronstein from Israel and tenors Andrew Mackenzie-Wicks and Daniel Norman from England. (It would be too long to list how many roles they impersonated; you can see the play bill below.)

In his minimalist stage-direction, the German Bruno Berger Gorski actually used only one scenic element: a long table. In the kitchen scenes its function was clear, in the other scenes it only had one purpose: to let the singers change clothes less visibly. (Apart from the table, we saw a huge Chinese carpet on the wall at the back, too.) The more ingenious and imaginative were the garish, bright costumes that made the distorted, hamming figures offset the empty stage.

*

The Golden Dragon is a complex work. In spite of the seemingly thin story, it takes time for us to embrace this piece; it makes us think over and over again even days after the performance. I myself also feel that I should see it again. It is a pity that there is no chance of it, given that this work of our world-famous composer is not performed in Hungary. So, it seems that it was a one-off chance, but at least we could get a taste of this notable piece.

Balázs Csák

***

Péter Eötvös:

The Goldan Dragon (Der goldene Drache)

Opera in one act, in English – Hungarian première

Libretto: Péter Eötvös, based on Roland Schimmelpfennig’s play with the same title

Translation, Hungarian subtitles: Jenő Jánszky Lengyel

Conducted by: Zsolt Nagy

Directed by: Bruno Berger-Gorski

Cast:

The young boy (the Little One) – Einat Aronstein

The woman over sixty (old cook; granddaughter; the Ant; Hans; Chinese mother) - Andrea Meláth

The young man (young Asian; waitress; grandfather; the Cricket; Chinese aunt) – Andrew Mackenzie-Wicks

The man over sixty (old Asian; Eva, the brunette stewardess; the boyfriend of the granddaughter; Chinese father) – Daniel Norman

The man (an Asian; Inga, the blond stewardess; Chinese uncle) - Kornél Mikecz

Israel Contemporary Players (Artistic Director: Dan Yuhas)